5/13/2016

Virginia Supreme Court Champions Windshield Obstruction TicketsHighest court in Virginia affirms traffic stop over a military base parking pass.

Windshield obstruction tickets are a significant source of revenue for Virginia. A divided state Supreme Court last week stepped in to ensure police continue to issue those tickets. State law mandates that every vehicle to have a three inch by four inch inspection sticker applied to the windshield, and many municipalities add the requirement of a three inch by three inch car tax decal. Nonetheless, the state Supreme Court majority insisted that a three-by-five inch military parking pass hanging from a rearview mirror represents a potentially deadly hazard.

"Although Code 46.2-1054 [the windshield obstruction statute] proscribes conduct few might think unlawful, its legislative purpose is far from trivial," Justice Charles S. Russell wrote. "The rear-view mirror, expressly permitted by the statute, is placed behind the windshield's center, partially obstructing the driver's view. Any opaque object suspended below it will probably obstruct the view to the driver's right to some extent. Any obstruction in that area can lead to tragic consequences when, for example, another vehicle backs out of a shrubbery-screened driveway ahead or a child darts out from between parked cars into a residential street in pursuit of a ball or a runaway pet."

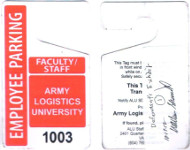

Loren Anthony Mason Jr wound up in legal trouble because he was a passenger in a green sedan that had a Ft. Lee employee parking pass hanging from the rearview mirror on March 3, 2012. The potential to write an easy ticket caught the eye of Waverly Police Officer Willie Richards, who was running a radar speed trap on Route 460 at the time.

The hanging tag lead to a traffic stop in which Mason was searched, and marijuana was found. Although Mason successfully challenged the legitimacy of the traffic stop before a three-judge appellate panel (view opinion), the full Court of Appeals later reversed the decision. The Supreme Court majority affirmed the latter ruling, pointing out that it does not even matter whether Officer Richards misunderstood the law or not.

"The test is not what the officer thought, but rather whether the facts and circumstances apparent to him at the time of the stop were such as to create in the mind of a reasonable officer in the same position a suspicion that a violation of the law was occurring or was about to occur," Justice Russell wrote.

Justices Cleo E. Powell and LeRoy F. Millette Jr found it disturbing that the majority creates a hypothetical police officer to justify an actual police officer's mistake of the law, citing the US Supreme Court's reasoning in Heien v. North Carolina (view case).

"The Supreme Court held that an investigatory stop based on a mistake of law can be valid, provided the mistake of law is objectively reasonable," the dissenting justices wrote. "Notably, in analyzing the issue, the Supreme Court did not look to whether a reasonably objective officer would have made the same mistake; rather it looked to the statute itself to determine whether the detaining officer's interpretation was reasonable."

The dissent argues that the officer's own testimony shows that he misapplied the windshield statute in an unreasonable way.

A copy of the ruling is available in a PDF file at the source link below.