11/26/2010

Federal Appeals Court Rules Against GPS TrackingCourt of Appeals for DC Circuit rules against warrantless GPS tracking of motorists.

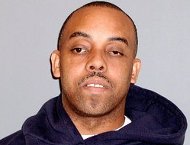

A divided federal court last week ruled that police could not use GPS devices to track a suspect without first obtaining a warrant. Nine judges of the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit considered the case of Antoine Jones who had been arrested on October 24, 2005 for drug possession after police attached a tracker to Jones's Jeep -- without judicial approval -- and used it to follow him for a month.

A jury found Jones not guilty on all charges save for conspiracy, on which point jurors hung. District prosecutors, upset at the loss, refiled a single count of conspiracy against Jones and his business partner, Lawrence Maynard. Jones owned the "Levels" nightclub in the District of Columbia. Jones and Maynard were then convicted, but a three-judge panel of the DC Circuit ruled that the US Supreme Court specifically stated in a 1983 case regarding the use of a beeper to track a suspect that the decision could not be used to justify twenty-four hour surveillance without a warrant. In this finding, the DC judges split with the Ninth and Seventh Circuits, which have no problem with police attaching tracking devices on any automobile at any time.

Those circuits, and the prosecution in the Jones case, argued that Jones was driving on public streets. Therefore, the GPS units merely augmented the senses of a police officer who would have been free to observe Jones's movements. In an August decision, the three-judge panel disagreed.

"We hold the whole of a person's movements over the course of a month is not actually exposed to the public because the likelihood a stranger would observe all those movements is not just remote, it is essentially nil," Judge Douglas H. Ginsburg wrote. "It is one thing for a passerby to observe or even to follow someone during a single journey as he goes to the market or returns home from work. It is another thing entirely for that stranger to pick up the scent again the next day and the day after that, week in and week out, dogging his prey until he has identified all the places, people, amusements, and chores that make up that person's hitherto private routine."

As a person would not expect the whole of his movements to be recorded, he has an expectation of privacy, the panel argued. This triggers the Fourth Amendment requirement for the police to obtain a warrant.

"A reasonable person does not expect anyone to monitor and retain a record of every time he drives his car, including his origin, route, destination, and each place he stops and how long he stays there; rather, he expects each of those movements to remain disconnected and anonymous," Ginsburg wrote.

The full court decided to uphold the three-judge panel's decision throwing out the charge brought against Jones because the evidence was obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

A copy of the en banc decision is available in a 90k PDF file at the source link below.